Going back to before the Sons of Liberty at the Boston Tea Party, white Americans have used Indians to articulate their claims of righteous authenticity. Notably, some of the white supremacist groups at the August 2017 “Unite the Right” riot in Charlottesville, Virginia, chanted “blood and soil” as they protested the planned removal of Lee’s statue. What did Lee mean by “American”? He invoked a definition of nationhood that the ancient Greeks and Romans and, later, the Nazis, also claimed: one was an American by virtue of one’s pure “blood” (a claim that one’s ancestors all belonged to the same “race”) and inalienable attachment to soil (or, the territory which white southerners, then and now, claimed they waged war to protect).

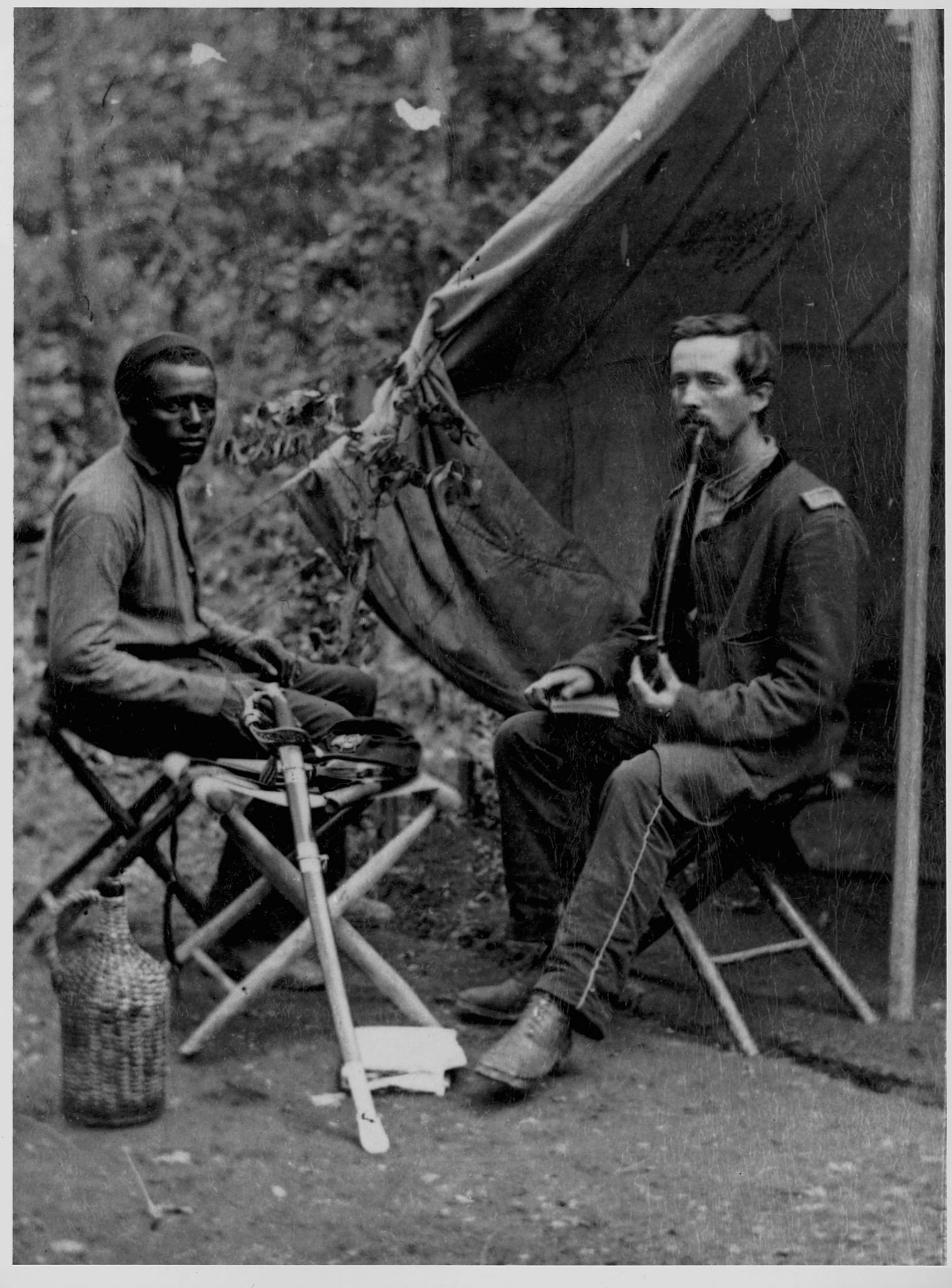

Parker simply extended his hand and replied, “We are all Americans.” 1 But Parker was not black, he was Tonawanda Seneca, a member of the Iroquois Confederacy from New York realizing his mistake, Lee stepped forward and offered his hand: “I am glad to see one real American here,” he said. At first, the story goes, Lee refused to shake Parker’s hand, mistaking his darker complexion for that of an African American soldier in Union blue. Grant at Appomattox in 1865, Grant introduced Lee to his personal military secretary, a man named Ely S.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)